Dou Jianyong (1976), also known as Dou Liangyu, is a native of Loling, Shandong province. He graduated from The Department of Chinese Painting of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts with a bachelor’s degree in 2000. In 2007, he graduated from the Department of Chinese Painting of Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts with a master’s degree, where he is today an associate professor.

Ink wash Art / Painting (水墨畫)

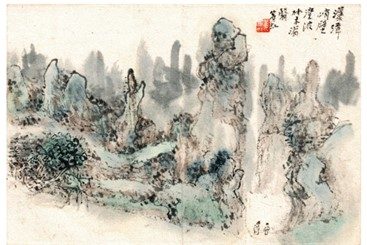

Ink wash painting is a type of Chinese ink brush painting based on black ink, such as in Chinese calligraphy, in different concentrations. It emerged in the Tang dynasty (618–907), when it overturned earlier, more realistic techniques. In the Song dynasty (960–1279), the genre flourished and spread out to Japan after Zen Buddhist monks introduced it in the 14th century.

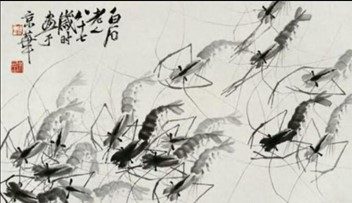

The traditional form of the Ink Wash is typically monochrome, using only shades of black, with a great emphasis on virtuoso brush strokes. It is common to describe the goal of ink and wash painting as an art aiming not simply to reproduce the appearance of the subject but to capture its spirit. The ink wash painting artist must understand its temperament better than its muscles and bones to paint a horse. There is no need to perfectly match its petals and colors to paint a flower, but it is essential to convey its liveliness and fragrance. Across more than a millennium. The majority of the works depicted objects and landscapes for the natural world; mountains, plants, insects, and animals. These points of emphasis became the source for comparison to the later Western movement of Impressionism.

In broad lines, these characteristics can be seen in works from the Song dynasty onwards, even including 20th-century artists such as Huan Binhong (黃賓虹), Qi Baishi (齐白石) and others.

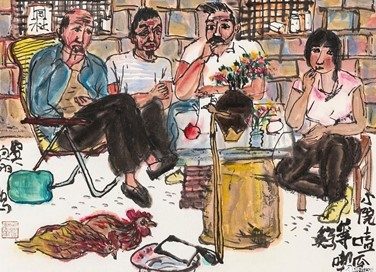

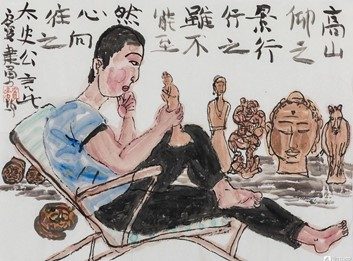

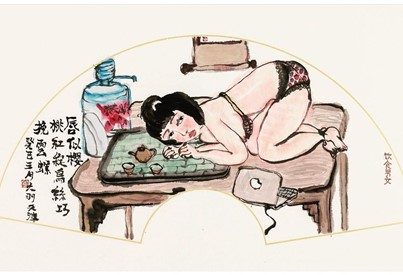

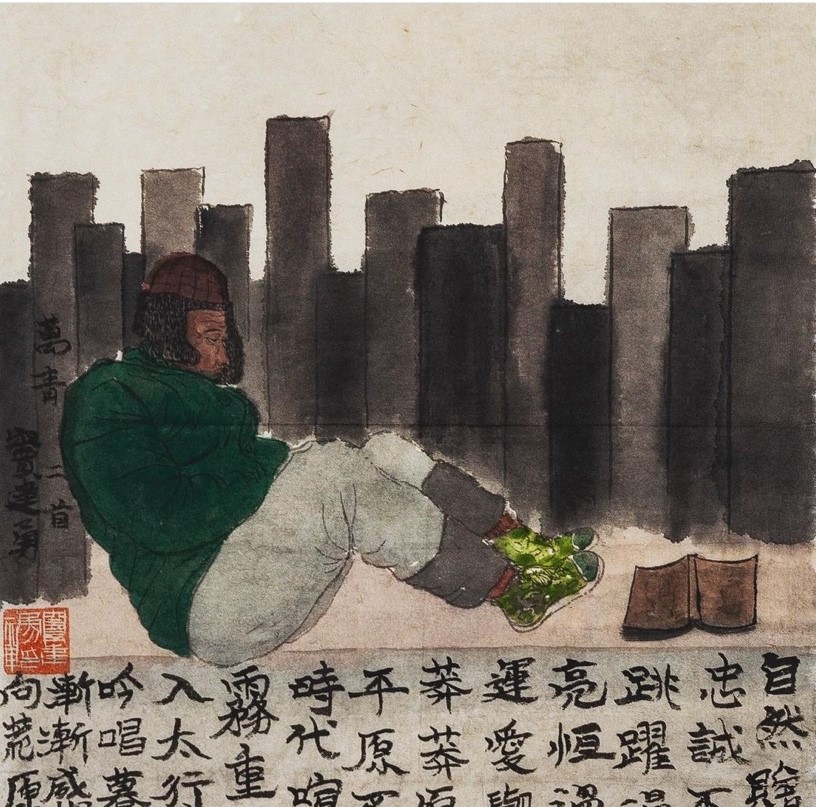

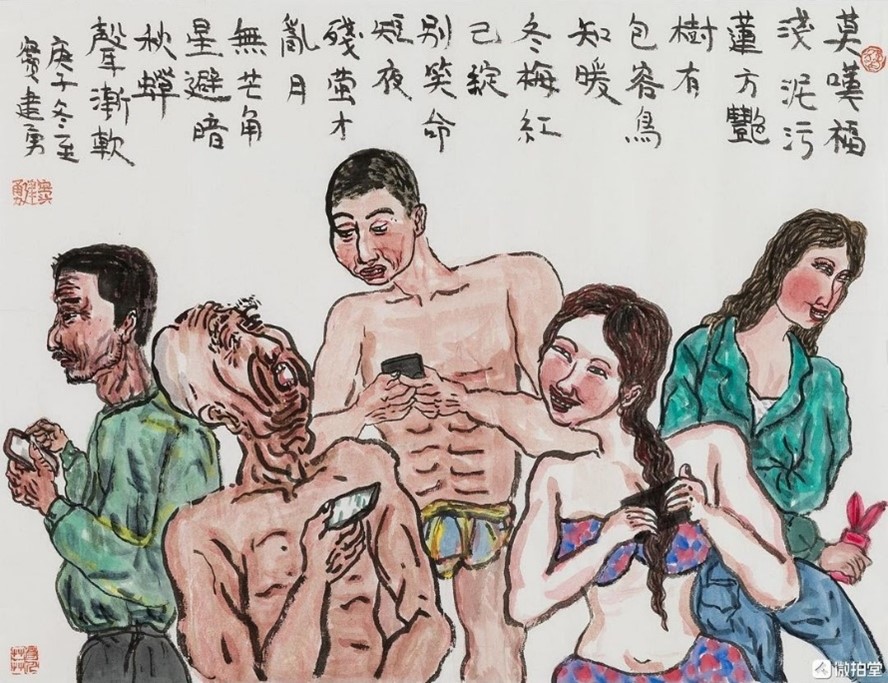

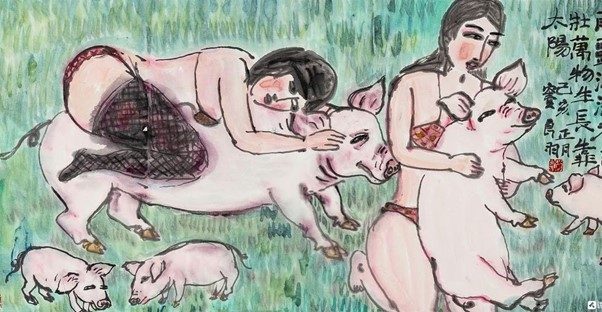

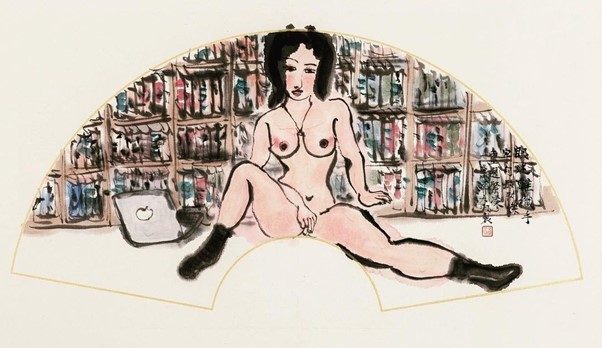

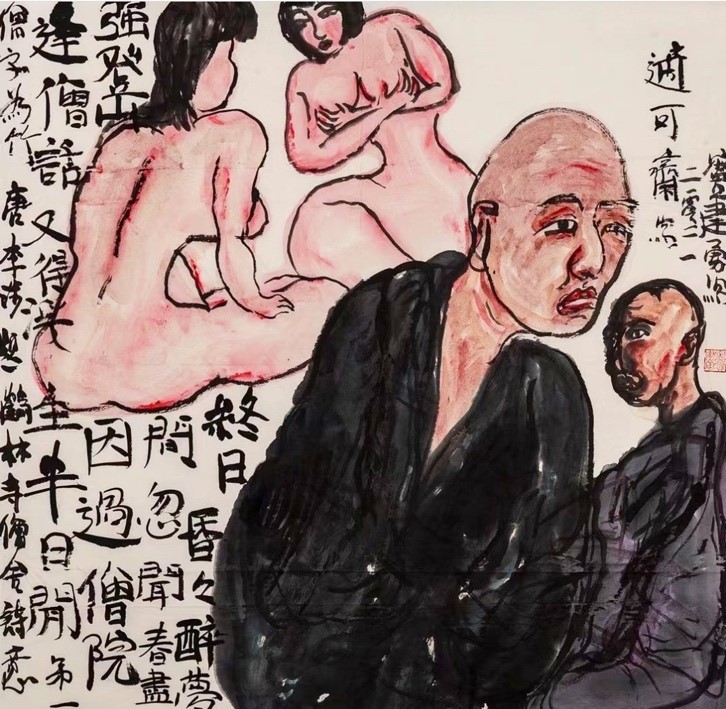

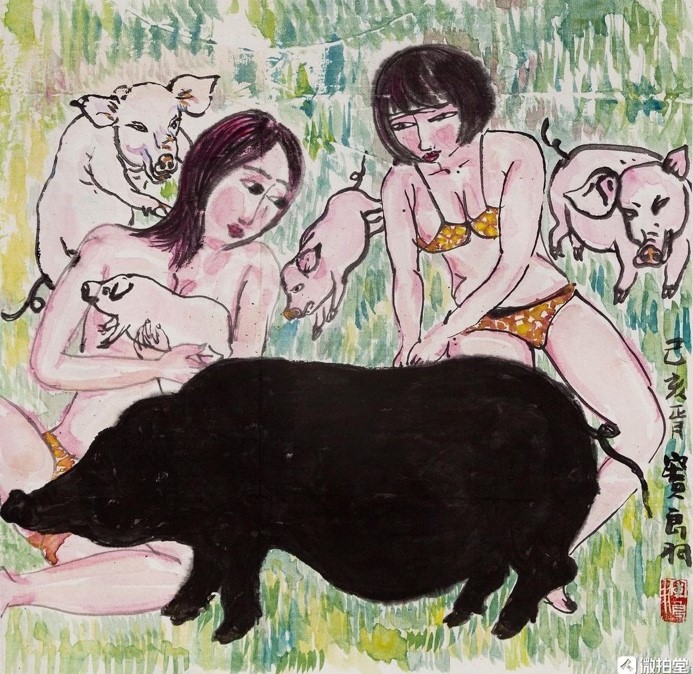

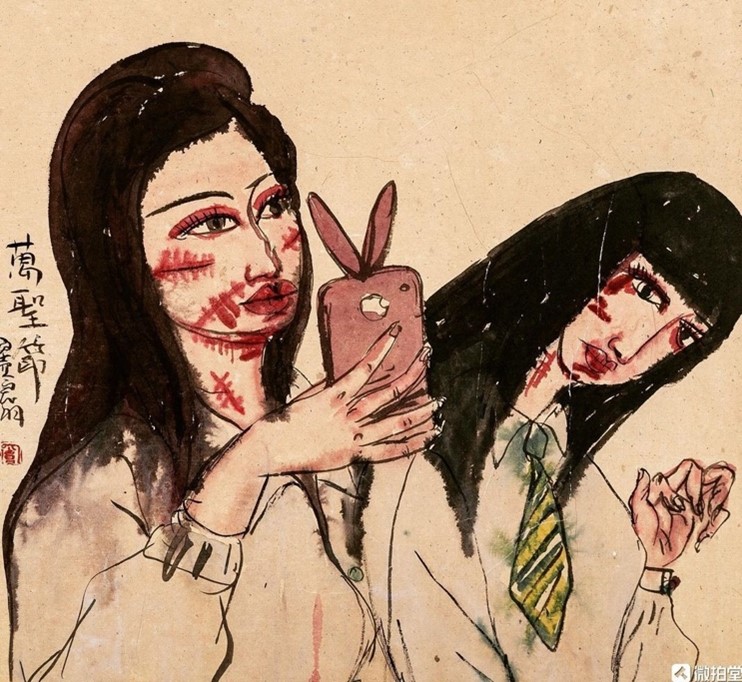

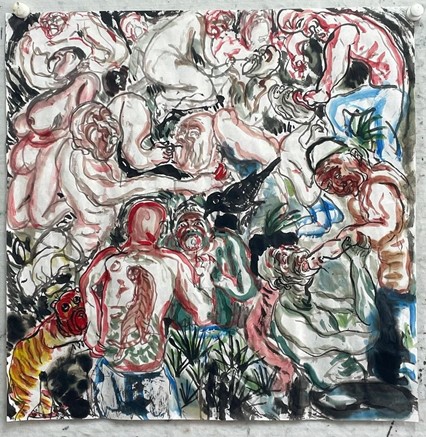

Dou’s work is much more descriptive than these earlier forms of Chinese ink wash art, separated by only a few decades from these modern artists. While some of the work does capture nature scenery, which relates it to themes from early and modern Chinese ink work, most of the work entails everyday social scenarios. These imaginary situations are highly detailed and complex. Many of the pieces contain animals related to village life, human figures, and religious figures.

“Often, when I think; ‘what do I want to focus on ‘? I become distressed, I decided not to draw the ‘what’? So there are those eating, drinking and other very ordinary life scenes, that are really my experience. Those people in the paintings are also my close friends in life.”

You are recognized with Ink wash on your websites and public posters. Do you see your work as part of an art-school or continuation of a school? And how do you see the development of ink wash?

“In China, ‘art schools’ are generally summed up by critics after the death of the artist. The ‘living’ means there are many possibilities for further development and growth. I do not deny that I have been influenced by some ‘art schools’ in the past, but what I want to find from beginning to end is the me behind the piece.

I like all forms of free and unrestrained artistic expression, and I also like works that are simple, sincere and naive. Writers have influenced me maybe more than painters; Wang Zengqi (汪曾祺), Tao Yuanming (陶淵明) and Su Shi (苏轼) . I was also influenced by San Mao (三毛) and Chiung Yao (瓊瑤) (two Taiwandes based female writers) as well as Tolstoy, Rousseau and others.

Traditionalist? Religious?

Ink Wash was historically particularly associated with religious and philosophical traditions prominent in China, such as the Chán sect of Buddhism (which became Zen in Japan), which emphasizes simplicity, spontaneity and self-expression, and Daoism emphasizes spontaneity and harmony with nature.

Ink Wash even influenced the practice of some of these traditions. For example: Within ink wash, the practice of Ensō, developed. This is a disciplined-creative practice of Japanese ink painting, associated with Buddhism, which is considered a self-realization method, a spiritual practice. Ensō, in the spirit of ink wash minimalism, are paintings of one circle, representing the beauty of imperfection.

I did not bring up the topic of traditions in my conversation with Dou, but my impression is that it is a theme he is busy with within his creative process, which he often brought up. When Dou speaks about his work, the essence of art, he continuously refers to essential principles from Daoist philosophy, which is also broadly associated with Ink Wash. He still sees painting as a culture, philosophy, and history carrier.

“This kind of art can also carry a lot of culture, history, philosophy and so on – metaphysical things. It is ineffable, unable to express in words.”

Then Dou quoted a line from the Dao Dejing (an ancient Daoist philosophical text):

“ ‘Where the Mystery is deepest is the gate of all that is subtle and wonderful’ (玄之又玄,衆妙之門).”

What do these four words mean to you? Pen, ink, paper, inkstone (筆、墨、紙、硯)

“For me, ink, paper and inkstone are the materials and tools for painting, as well as my spiritual home, my muse and my religious belief.”

How would you relate to the various references to Buddhism which appear in your work?

“I have to say that most Chinese have no faith, or faith is something they use when they need it. Those Buddhas and monks are also the kind of people who often appear in my mind. Maybe they represent seeing through the world of mortals and staying away from the secular world (abstinence). Maybe they represent a kind of gazing at the souls of all living beings in the world.”

Rural-Urban

In the 1990s, urban culture was a prominent subject of social discussion in China, as various social and economic reforms have been introduced, including rapid urbanization. Contemporary art has entered a new period of development in those years, with a new generation of artists emerging in film and television, literature, and art. As an artist born in the 1970s, how do you view the impact of urban culture on art? And its effect on you?

“I watched a lot of martial arts movies from Hong Kong and Taiwan when I was a senior high school student in the countryside such as The Swordsman 1 and 2 (Xiao Ao Jiang Hu笑傲江湖; 1990, 1992). That chivalrous spirit and ancient traditional road wisdom portrayed in the film characters seem to have some influence on me (the story of the films in based in the Ming dynasty- 16th Century). In my eyes, the city is already in a state of illness, with ugly buildings like monsters. These old traditional qualities are gone.

Originally, My favorite weekend shopping is in second-hand bookstalls. These second-hand booksellers from the Second palace were expelled to the Drum Tower and then expelled to the cultural street and then expelled to the riverside until disappeared. The big city will not give something like a small second-hand book stall their deserved place.”

As an artist who came from the countryside to live in the city for a long time, your childhood life has a great influence on you, but does this emotion change with age?

“The change is that the impact of the memories seems to be stronger. For example, aesthetics, diet, work and rest, meditation, and dreams all revolve around the essence of the rural life of childhood.”

Provocation

Placing naked female figures on scrolls and wrapped army Jackets. Is that done to break tradition? To provoke?

“It seems that sex is hard to avoid for painters as it is for writers to avoid sex in their novels. but painters who specialize in landscapes or flowers can leave this question aside for the moment. I clearly intend to enhance the sexual characteristics of the female in the picture. The female figures represent a kind of sexyness, mystery. Sometimes lewdness. Sometimes I treat them as dignified and holy. Their appearance is more from the fantasies and dreams of my youth.”

Liminality- Ink Wash Between Life and Death

In July 1985, Li Xiaoshan, published the controversial article titled ‘My View on Contemporary Chinese Painting’ (Dangdai zhongguohua zhi wojian ) about the state of Chinese ink painting at that time. The article aroused much debate and became one of the most important critical essays of the 1980s. In the article, he stated that ink and wash painting had reached a “dead end”. Indeed the question for modern ink painters has been how to define “Chinese painting” (zhongguohua中国画) or “national painting” (guohua国画).

It has become common to try and categorize Ink and Wash paintings created after the Cultural Revolution into types like customary, expressionist, documentary, or experimental, each one according to the techniques or traditions they use and are based on. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, however, Chinese art has been interfused with other genres such as performance, photography, and video, with artists occupying more than one field of artistic interest. Dividing contemporary Chinese painting into four dogmatic categories thus proves to be a problem, especially since growing globalism in the art world pushed the amalgamation of art even further.

Liminality is in various ways what characterizes the themes in Dou’s work. In betweenness of religiosity and secularity. Traditionalism and provocation. His work is situated in the border zone of urban and rural life and reflects modernity with alternations of acceptance, hate, love, and nostalgia. It may be connected to a more general liminal reality of ink Wash art in the 21st century, as it is challenged by technology, postmodern and meta-modern conceptualizations, and other accelerated processes that influence the art world, society, and our creative imagination. Ink wash might be in a liminal space, between life and death, which might linger to be its future.

Do you consider yourself a contemporary artist or a Chinese painter?

“It doesn’t matter. I look at the world with kindness and poetry.”

What is Ink wash art for you? Does that exist?

“There is no ink art, only art. If anything, it simply means works of art made of water and ink. The title doesn’t seem to matter that much, the key is how much art is there in the work?

Contemporary Chinese ink painting is indeed increasingly diverse. Just as the rise of smartphones had changed photography. People can use the ink in painting to form expression to their joys and sorrows, but they can also use the form of a short video to attract attention. I think what is important is not the form or medium, but the artist’s intellectual depth. These determine the quality of the work. Because of pursuit for this quality, the ‘ancient’ Chinese painting art has not died.”

Like our stories? Follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Contributor: Kai Shmushko is a researcher based in Amsterdam and affiliated with Leiden University and Tel Aviv University. She writes about religion, culture, art, and philosophy focusing on modern material realities and imaginations of Chinese societies. Her work explores aspects of these topics based on extended fieldwork periods in the Chinese sphere. Her interests also include post-Mao religious and artistic expressions and the interactions between religion and culture.

Images Courtesy of Dou Jiangyong