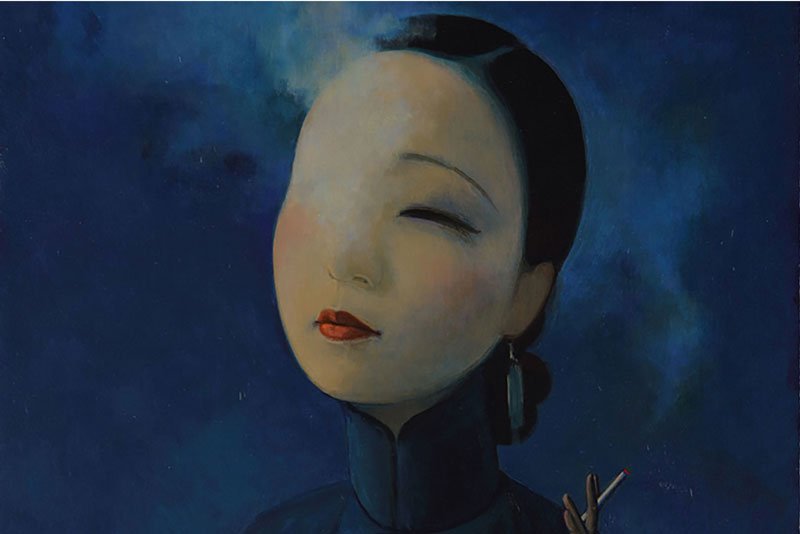

Portrait of Chinese painter Liu Ye

Artworks by Liu Ye contrast extensively with the typical characteristics of the Cultural Revolutionist artists, much of whom dominated the scene of contemporary Chinese art. Despite being born during the period of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Yu does not bury his brushes with political and societal undertones like his contemporaries. His art, on the other hand, dives deep within his inner world and depicts the language of his mind.

Most of Liu’s paintings feature characters that are universally familiar. He produces stylized depictions of children, often with highlighted characteristics such as their round faces. These he puts together in colorful compositions of typically reds, yellows, and blues. The beauty of Liu’s works lies in how it demonstrates historical figures, cultural moments, and more serious subjects in a seemingly innocent and simple frame. A few art critics believe this simplification of serious subjects come directly from Liu’s childhood experiences.

Growing Up Amidst the Cultural Revolution

Before the Cultural Revolution took up China in full stride, Liu Ye was born in the city of Beijing. His father used to write children’s books but with the government restrictions and regulations, most of his time was dedicated to working under the government.

During this time, many books were officially banned from production and distribution. This blacklisting of books disabled many from reading great works of literature. Yet, Liu was spared from this restriction because his father had secretly shelved away a few books that were monumental in Liu’s artistic influences in the future.

If you are interested in more about Liu Ye check our artbook page.

Among these books were illustrated copies of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and Anna Karenina. There were Hans Andersen’s and Alexander Pushkin’s fairy tales along with a handful of other blacklisted literature. Today, many of Liu’s works resonate with stories from classical literature and the influences of children’s literature are vividly imprinted in nearly every one of Liu’s art.

The Development of Liu Ye

When he was 10, Liu showed great interest in drawing. This led to his father introducing Lui to an art teacher named Tan Quanshu. For 5 years, Liu remained under the patronage of Tan where he learned and improved on basic artistic compositions and techniques. This progress, however, was abruptly halted when Lui was diagnosed with amblyopia in his left eye.

While it was a moment in which Liu was obstructed from his love for painting, it did not stop him entirely from pursuing his dream of being an artist. Instead, Liu continued to study art under Tan’s guidance and soon enrolled into the School of Arts and Crafts in Beijing at 16 years old. There, he joined the Industrial Design department and learned a great deal about western modern art.

German Influence

These moments in time built the initial foundations of Liu’s artistic style while the major impact on his art grew when he traveled to Germany in 1989 to complete his undergraduate studies and later, Master’s degree in Fine Arts at the Berlin University of the Arts.

As he lived in Germany, Liu lay witness to historical events such as the Fall of the Berlin Wall. He was also exposed to many of the European wonders, studying Western modernism in great depth by analyzing works by Paul Klee and Johannes Vermeer.

His work began to resonate with the qualities of Vermeer, Klee, and Mondrian as he focused mainly on Dutch portraiture. In contrast to his Chinese contemporaries, Liu remained a stranger to modern Chinese art as he captured more universal ideals such as beauty and hope in his paintings. He had even commented that ‘Seeking beauty is the last chance for human beings. It is like a shooting at the goal; it arouses an emotion that is wild with joy.’

Liu’s Kaleidoscope

Even though Liu’s artwork was dominated by European themes and ideas, pertaining mainly to German Expressionism, it changed immensely when he returned back to China in 1994. His early canvases were compact with gloomy atmospheres and elements of surrealism but his return to China allowed to create a more unique style in his art.

Liu began to see himself as a child rather than a formative adult. His drawings held figures of children and his favorite cartoon character, Miffy the bunny. He also brought in more settings in contrast to his earlier backgrounds of rooms and theatres. Furthermore, his use of colors developed from muted tones of greys and blacks to primary colors. This distinction can be seen in two of his earlier and later drawings, the 1994 Angel before Mondrian and the 2001 Mondrian in the Afternoon.

Therefore, as Liu’s surroundings changed so did his kaleidoscope of artistry. His Western influences are still prevalent through his artwork and he continues to draw inspiration from great figures in Western art and literature. For instance, his 2002 re-imagination of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in Romeo sets the hero in a modern setting where he wields a gun instead of a sword. This is the same for other paintings such as the 2009 Mozart and the 2011 Pinocchio.

Perhaps the reason why Liu is such an international figure in art is that his works capture contemporary motifs and figures and transfer them into his personal reimaginations. This adaption of character is a great storytelling feature maintained by Liu, where he aims to define human nature through the modern and internationally recognized archetypes.

Liu Ye in Current Times

Ye has had numerous international and national exhibitions throughout his life, most notably in the Johnen and Schöttle in Cologne, Germany; Sperone Westwater in New Work; the Schoeni Art Gallery in Hong Kong; and the Venice Biennale.

Other than these, he also maintains permanent art collections in the Shanghai Art Museum as well as a few others. Liu Ye currently lives in Beijing, China, and continues to work there while having been recently announced as David Zwirner’s first Chinese collaboration.

About his collaborator, Zwirner remarks, ‘To me, Liu Ye’s work is a unique and surprising conversation between the East and the West; we often recognize Western imagery, such as objects and color, but conceived with an Eastern understanding of space. Whether small or large, his (Liu’s) play with space and scale radiates a sense of permanence and wisdom to the human condition.”

psst… I hope you liked this Portrait of famous modern Chinese artist Liu Ye. If yes give it some social love and pin, like or share. Much appreciated!